Hope for AI

Far beyond image filters and grammar checks

This is a companion article to the previous issue, “Fear of AI.” That article explored a number of concerns about what might go wrong with AI; this one is about opportunities.

Sometimes we have a sense that the world used to be a better place. There’s a feeling that folks used to get it right. It’s an archetypal narrative we repeat to ourselves: Humanity once had it all, and we screwed up. We ate the apple; we invented potato chips and ice cream, capitalism and corporations.

It’s true that we, as a species, make plenty of mistakes. At the same time, things often improve. Socrates decried the advent of written knowledge, predicting that writing things down would cause people’s memories to degrade as they relied more and more on recorded information. He also worried that the comprehension of ideas would decrease since reading can give you the sense that you know a topic when — in actuality — interactive conversations and hands-on experience are far better teachers than reading alone.

The most interesting thing about those ancient claims is that they’re somewhat true. Socrates warned us of the consequences of a new technology — and I can’t say he was wrong. But do you think humanity made a mistake by inventing the written word? In retrospect, a more thoughtful response is to agree with Socrates — and to see that the tradeoff was worthwhile. Humanity is better overall with writing than without, although some aspects of our former society can be said to have gotten worse, such as (I suspect) the quality of our memories for verbal details.

The outlook of this article is not to disagree with naysayers of AI. So much of what worries people is based on reason; many of their concerns deserve consideration and action. Rather, my central tenet is that we’ll do best to foster nuance, curiosity, and hope. Our perspective broadens when fear becomes prudence. Greatness is a product not of hesitation but of passion for what lies ahead.

A New Shape of Life

I’ll begin with what I consider the most progressive change that AI may bring about: a new kind of mind. It’s such an enormous shift in reality that no one can accurately predict how valuable this might be. Did Maxwell foresee the internet?

The largest leaps forward in the history of our species have been those that brought entire societies forward along the hierarchy of needs. Fire gave us more efficient access to nutrition in cooked meals, freeing up energy previously used to live on uncooked food. Labor specialization within groups further contributed to the efficiency of our efforts to survive. As civilization progressed, other milestones — such as the introduction of antibiotics and widespread literacy — have shrunk the list of worries or expanded the opportunities available to almost everyone.

A new kind of mind is a sea change. If we can see a digital entity as a different kind of person, then suddenly so much about our world becomes less singular and more diverse. Our concept of a lifespan, of a generation, changes. We’re granted a new realm for the creation of life, for evolution itself.

As we observe the unfolding mechanics of digital life, we can also see ourselves in a new light. Fish, first emerging from the ocean, began to comprehend not only air, but water as well. I’m sure there will be much to learn about what is possible, and about the assumptions we have accidentally made about the world because we knew of only one kind of mind.

To focus on something concrete, consider the workings of the human brain. Even if our most-used neural networks operate differently from the brain, they’re likely to afford breakthroughs in our understanding of how minds work. For the first time, we’ll have some version of an advanced brain in a jar — one we can study without hurting or dissecting anyone. In fact, one we can observe with unique purity because we’ll have captured the full context of the system. This can grant us the elusive ability to completely reproduce and study mental states.

With this new awareness about minds and their implications for human brains, we’ll be able to more scientifically understand mental ailments, such as depression, as well as available mental improvements, such as deriving strategies for thriving communities or happier individuals.

At this point, you might think I’ve gone off my rocker. I admit that I’m looking far, and what’s farthest ahead is the hardest to see. But the skepticism that’s useful for short-term models of the world is blind to great shifts in reality. While we may proverbially believe in nothing but death and taxes, there is something far more certain — the future will happen.

Let’s move closer to today and see what’s in a lower orbit. But I’ll hold on to my optimism and keep looking for new ways to move forward, rather than faster horses.

An Interface with the World

When Socrates complained about writing, and Plato wrote that down, things were changing. With written knowledge, people can learn directly from the authors of any time and place. Recorded knowledge is robust to the noise of history. When Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453, waves of scholars emigrated from the city, bringing with them the ideas stored in ancient Greek and Roman manuscripts — ideas that had for the most part been forgotten throughout Europe. This preservation and restoration of scholarship gave birth to the Renaissance.

Writing, literacy, and education have created a secondary mode of evolution based on mental genes — genes composed of the accumulated wisdom of humanity. There’s a shared global consciousness that we contribute to and learn from. From this perspective, our knowledge-oriented milestones — like the creation of the internet, or the introduction of Google-quality search engines — can be seen as tools that more effectively connect individuals to our shared consciousness.

In that vein, AI has the potential to more efficiently bring anyone closer to the resources we share. At an abstract level, one use of AI is to act as a universal librarian — a kind of friend who happens to know everything on the internet, and wants to help you accomplish whatever you want. Having such a friend at your disposal would be a kind of superpower. They don’t intrinsically create new knowledge (I’ll talk about research after this), but they do provide a vastly improved interface with everything that already exists online.

Let’s be more specific. As one example, when we use a search engine to look for a recipe, our primary goal isn’t to use a search engine. In fact, our goal is not even to find a page with a recipe. Our goal is to make a meal. Much of the internet is currently fueled by this friction between our day-to-day goals and our achievement of those goals. We can replace search engines with an AI that simply tells us the answer. In fact, ChatGPT has already started to do this.

When we do have a goal on a specific site, it’s generally up to us to quickly learn the site’s specific interface to accomplish that goal. Sometimes, such as when we buy a product on Amazon, the incentives are aligned and that goal is straightforward to achieve. In other cases, such as when I need to change an airline reservation, I may have trouble accomplishing this online, or talking to a customer support person, or — importantly — talking to someone who’s both competent and has the authority to help me. A key element of this friction is that every single customer support worker has to be independently trained and supported, and different tiers of workers often have different levels of authority to help people. If customer support becomes AI-supported, then every interaction you have with a company can be with their best and most-authorized interface.

We can extrapolate from customer support to many other person-organization interactions. For example, if I want to find a birthday gift for a friend, an AI can understand a description of what I know about my friend and put together a highly personalized list of gift ideas. Scheduling appointments online can be made more pleasant because an AI can quickly understand a fuzzy English description of when you’re available: “Thursday evenings and Saturday mornings, but if those don’t work, maybe a Sunday afternoon.” Pages or sites that teach you something new could be equipped with an AI model that answers questions in real-time as you learn. In general, wherever there could be an ad hoc online interface to any service, we could replace that with a natural language conversation.

So far I’ve been imagining the applications of a smart, internet-aware friend. But what if instead we have a smart, internet-aware version of yourself? An AI that understands what you, personally, like and care about. For example, instead of an overwhelming email inbox, or an onslaught of phone notifications, you might instead see exactly the subset of pings you care about at any given moment — the subset you would have chosen if you’d reviewed everything carefully. An AI that knows you could let you know when you’re about to be late for an important meeting, and talk you through a moment of procrastination or a challenging decision. Instead of the smart speakers of 2015, think of Iron Man’s Jarvis.

The End of Logistic Complexity

And how might we build all this?

Maybe we won’t have to. Let’s move away from interfaces available to everyone and focus on tools that can help with specific jobs. I understand programming well, so I’ll focus on that job as an example, and then we can extrapolate.

If I ask ChatGPT to write a simple program, it often succeeds. If I ask it to explain or fix an error message in my code, it can do that as well. GitHub’s Copilot can write functions for me based on a short description of what I want it to do.

What’s around the corner is a mode of creating programs in which coders can focus almost entirely on design instead of the details of implementation. We can understand this future in some detail. Let me decouple two sides of programming.

Bugs in code come in two flavors: The more common type is a mistake in translation from thought to source. This includes silly things like syntax errors, but also cases where you forgot an edge case, didn’t assign a value to a variable, or set up a race condition by forgetting to use a mutex. This kind of bug includes any error based on a divergence from your core design. You can fix it by bringing the code closer to what you had intended. The other kind of bug is a design flaw. This is where you decided to build something a certain way, and only later realized that the design itself is not what you wanted after all. This is the more pernicious error because you’ll probably first spend time looking for a translation mistake of “type 1” before realizing it’s not the code, it’s you. For example, you might program a concurrency framework based on a mistaken assumption around what was a safe way to avoid race conditions. Once you realize your mistake, you have to redesign the system, not (just) the code.

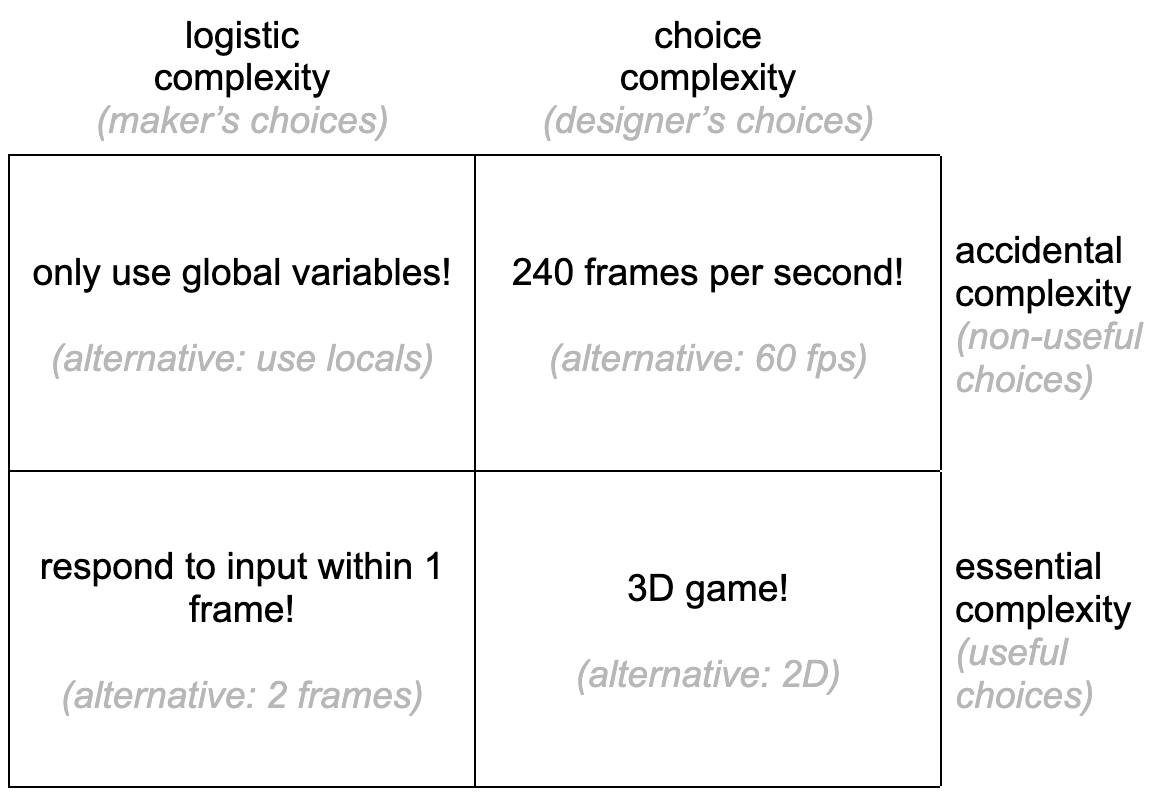

Along these same lines, I’m going to use the term “choice complexity” to indicate the work needed to design something, and “logistic complexity” for the work needed to translate a design to reality. These sound similar to the terms “accidental complexity” (complexity that you’ve added by decisions that could have been made better) and “essential complexity” (complexity that was unavoidable) as introduced by Fred Brooks in The Mythical Man-Month. He was talking about a different split, though; he was judging the impact of choices based on whether they added work without adding value. When understanding AI workers, it’s more useful to split up the choices by the chooser’s role: designer or implementer.

To clarify the concepts, here’s a simple grid of example choices that might be made when making a video game:

The point is that implementation is not typically what we really care about doing ourselves, and happens to also be something that AI will be able to do. The future of coding isn’t about code. It’s about design.

What about other jobs? I suspect AI can become a next-level tool for any task that allows a split between design and implementation. Curiously, I don’t think that high-quality writing — such as writing a book — allows for this split. But many jobs do: coding, writing less literary pieces (such as documentation or contracts), analyzing data, using semantic databases (such as comprehensive or nuanced medical information retrieval), executing financial strategies, making blueprints from abstract architectural goals, converting fashion sketches into digital patterns, or creating urban simulations to assist with city planning. I’m undoubtedly missing most of the pie, but you can see the shape of this hope: that many of our jobs evolve dramatically, shifting away from the details we’re less interested in toward the conceptual.

Research

If we continue along the trajectory from trivial details to abstract thought, we find ourselves at the frontier of discovery.

This is where things get interesting.

The biggest problems we face as a species are ones we can address once we better understand the systems involved. Our planetary ecosystem is suffering as a result of climate change; people still suffer from ailments we’ve studied for many years such as cancer and heart disease; political instability threatens to overshadow our other worries. Worldwide hunger remains a serious problem, with over 2 billion people living in a state of dangerous food insecurity.

An AI model that can think and talk cannot directly solve any of these. Taking a step back, however, we can see that research can help. We can find new methods to create cleaner power; we can discover new treatments for diseases and unhealthy conditions; we can better understand political gravity wells and points of friction between current decision-making structures and find better ways to choose social and economic policies. When we discern the mechanics of communities and how to move them towards healthier policies, secondary benefits become possible, such as improving the availability of food.

My claim so far is simply that research itself is a path toward a better world. In the companion to this article (“Fear of AI”), I described research as a necessarily incremental process — the accumulation of many small ideas. AI can help by dramatically increasing the number of minds working on these ideas. Beyond a simple increase in the number of researchers, we have the potential to gain a multitude of minds of the best caliber. If one AI is found to be the best researcher in a certain field, why not run hundreds or thousands of that same AI?

It’s a simplification to assume such a basic relationship for the creation of new knowledge: that more researchers means more results. There are bound to be complexities, such as the challenge of creating an AI that can match our current quality of research; or the difficulty in getting AIs to work together, let alone to work in tandem with their human counterparts. And yet, it’s common sense that having more researchers is a good thing.

Take one extreme form of research: pure mathematics. In this case, it’s possible for a single mind to begin with a problem, arrive at a solution, and have confidence that the solution is, in fact, correct. Such confidence is not as easily found in other fields, such as in medicine, where a new approach must be tested before it has even a chance of being trusted. Such purely mental work provides clear opportunities for AI-based researchers to contribute to a field. But I see no reason why AI-based research needs to be restricted to abstract mathematics. Indeed, an AI researcher could propose theories to explain observations from physical experiments; suggest protein structures as part of the search for new drugs; design experiments to test theories of psychology. Anything a human can do intellectually with pencil and paper — which is, after all, quite a lot — an AI researcher may one day be able to do. The possibilities for illumination are immense and exhilarating.

Into the Unknown

While I’ve put in a serious attempt at understanding what’s next for us and the arrival of modern AI, like any predictor of the future, I’m destined to get some things wrong. I have the most confidence in what I say is possible or impossible — the possibility of AI-based research, and the impossibility of infinitely-fast superintelligence. What I’ll probably get wrong is not in what I do say, but in the lines of development that I’ve missed. There will be brilliant ideas I haven’t even dreamed of.

While any prediction of the future is imperfect, this moment justifies optimism because the recent advances of transformer-based AI — things like stable diffusion and GPT — are not destinations. Just as the first transistor only hinted at the possibilities beyond it, this stage of AI is itself a spark that starts an engine. Yes, we are finding our way as we go, and our path is yet to be seen — but it is the way ahead. Fear holds us back; hope moves us forward — our sense that the world before us can be a better place.